Pte Frederick Edward White, NX4726

(Enlisted 12 October 1939)

The following article from the Cooma Express was forwarded to the Committee by Frederick White’s daughter and she noted that:-

on the 18 March 1941 he embarked for service in Greece with 2/3rd, he was a signaller. His service record gives few details, but he was blasted out of a culvert on Crete and was very deaf as a result.

Article Published in the Cooma Express

Monday 24 November 1941

THE CAVALRY ON CRETE

PLANES AND PARACHUTES

THANK GOD FOR THE NAVY

In the following narrative, simply but starkly written for “Express” readers, Pte F.E. White, gives a first hand account of his experiences as an Australian soldier who passed through that strange campaign. Credit is freely accorded to the New Zealanders, the Navy, and the native born Greeks.

Pte. White writes:-

SOME SIDELIGHTS ON CRETE

Now that all the tumult and shouting about the gallant but unsuccessful fight for Crete has died away, I thought that you might be interested in a few incidents of some of the action that took place on that blood soaked island, which so far, I have not noticed in any of the articles that I have read on the subject. They are well worthy of mention and are things that I, personally will always remember.

IN CRETE BY ACCIDENT

When the first parachutist landed, our battalion, which actually was a composite battalion, being made up of remnants of the brigade after the Greek evacuation, had taken up a position right on the headland of Suda Bay. We shouldn’t have been on the island at all, as a matter of fact, but the transport from Greece was sunk by dive bombers and we were picked up by a destroyer, which had more to do than carry worn out soldiers about. As most of our gear had been lost or abandoned we were very lucky, in one way, that it was almost a month before jerry got to work on us seriously, giving us time to re-equip ourselves to some extent. We finished up with American rifles- Springfields and Remmingtons- God knows where they came from, of 1918 vintage. We had a few machine guns and a few grenades, but that was about all. It says something of British thoroughness that we were able to get even those because every ship that even came near the island had hell bombed out of it. We had sufficient food and even a drop of beer now and again, and what with the local production of eggs and potatoes we weren’t badly off in that respect. What we didn’t have was tobacco. It was terrible to see men ratting through their pockets for the hundredth time in search of a stray bumper. We finished up smoking tea-leaves and I was never so glad in all my life as when, on the destroyer – an Australian one – that took us off the island, a sailor gave me a cigarette as I came over the side. Incidentally, there is no rivalry between the Navy and ourselves now – we thank God for them.

QUIET BEFORE THE BLITZ

At first, except for air-raids, things were comparatively quiet, and as we expected to be relieved, we weren’t worrying very much and were just taking things quietly, although we went about armed all the time. Near where we were camped was a village of some size and as they had a wireless down there, a detail of us used to get permission to go down to listen to the news. Often, in the middle of the BBC’s statements of “slight activity over England last night” the Luftwaffe would cause us to dive down the nearest wine cellar, and we knew why. Still, this particular village, with the waters of the bay lapping right at the doorsteps was not bombed while we were in it, but I heard later that it was blasted off the map. I don’t know if it is true, but in the view of what I saw later of the Luftwaffe’s methods, it is quite probable. The villagers themselves were very friendly, and we were a perpetual pleasure to the kiddies, who tried hard to master the meaning of “cobber,” “digger,” and “two-up.” The latter we taught the old fellows with a fair amount of success and schools were flourishing quite openly towards the end. Most of the young men were in the army and consequently there wasn’t much gaiety. The ubiquitous donkey was to be seen everywhere, patiently bearing his sometimes heavy burdens; I think one of the most beautiful pictures I have ever seen was a little she-ass and her foal quietly grazing in the fields with a huge burnt out German bomber a crumpled mass just a few yards away. Beauty and the Beast – in a different setting.

THE PARACHUTISTS ARRIVE

The afternoon that the parachutists first came over, I together with two other chaps, had been sent to the other side of the village to draw some water. We had a donkey, an old wagon and about fifty two gallon tins to fill from a spring. Although jerry planes had been flying over all day except to keep a watchful eye on them, we didn’t let them worry us – they were all too familiar by this, and it didn’t take us more than the usual time to fill the tins and turn homewards. It wasn’t until we were in the village that we realised that something was wrong. Everyone was standing, white-faced, around a dilapidated old bus that ran daily from Canea to the village and had just arrived. A man was talking, and even the usual cheerful kiddies were hushed. Then we saw a remarkable sight – old men of between sixty and ninety, break off, walk into the houses and re-appear with rusty old shot guns, muzzle loaders and even a few old powder and ball percussion-cap rifles, as well as with pitch-forks, long poles and wicked looking knives. At that moment, we were the only soldiers in the village and the chap who we understood to be the Mayor or its equivalent saw us and came up to us. Speaking in a halting kind of English he said – “German parachutists have landed!” Then he looked at his people and said “We are ready!” They were Greeks and proud of it. The Huns might starve them and kill them, but they’ll never conquer them – I’m convinced of that!

SKY FULL OF PLANES

Well, we didn’t waste any time getting back with the water – the patrols were out already and we were asked to produce our identity discs and pay books half a dozen times along the road. We learned in Greece all about Fifth Column activity – Germans in Australian uniforms were found – and shot -several times. Back at the unit we didn’t find anything abnormal going on, unless a tenseness in expression in the men’s faces could be called that. But there were changes – rifles had been oiled, ammunition in pouches were close by and grenades had been distributed, as had emergency rations. We never knew when we would have to start shooting, but we were ready. That night armed patrols crept around the paths and orchards but except for the dim rumble of gunfire and exploding bombs in the distance with occasional brilliant flashes, nothing untoward happened. The next day conferences were held and we prepared a few more positions. Reports came through of wholesale annihilation of the parachutists and that everything was under control. The sky was full of planes, swarms, literally hundreds of dive-bombers and twin-engined bombers cruised over our heads, while the anti-aircraft batteries on the ground threw everything at them except the guns. The sky was continually full of bursting shells and puffs of black and white smoke. Out on the Bay, dive bombers, again and again, made savage, furious, but more often than not, futile attacks on the ships and often we saw one of them plunge into a welter of spray and sink immediately, either were shot down or unable to pull out of a dive. Needless to say we cheered every time. It was on this afternoon that our bitterly, but wrongly abused Air Force put in an appearance. Not knowing the facts, we couldn’t understand why we rarely, if ever, saw our own planes. Poor devils, they weren’t to blame, but we could die of mortification when we saw all those Jerries and rarely any of our own. We learned later that whole squadrons sacrificed their lives to help us, but at that time we honestly believed we had only two Hurricanes and a game but slow old Gladiator on the Island – that’s all we ever saw.

TWO LONE HURRICANES

Well, on this afternoon, three twin engine bombers were playing follow-the-leader flying around and around in a small circle and doing up our particular grove of olive trees with their machine guns. Whole streams of bullets were whipping through the trees and churning up the soil in close proximity to me, and I wasn’t any too happy about it. Then, to our amazement, two hurricanes popped out of nowhere and in less time than it takes to write this, all three bombers were on fire and on their way to the sea. One pilot jumped out, but his parachute didn’t open and he whistled to the ground like a bomb as he fell. I saw him afterwards and it wasn’t very pretty. The hurricanes dived on one plane each, put a burst or two into them and both sailed into the third one. We cheered like maniacs, but that was the last time, on that island, we saw our planes. Just what would have been the outcome had it been possible to give us fighter support I don’t know, but my guess is that we would have been there yet.

NEW ZEALANDERS FIGHT

The next day we got the reports of heavy fighting going on but everything under control. We heard the Kiwis were putting up a great fight, and when the history of that campaign is written, we shall see the Kiwis have won immortal glory in those terrible days. We were still watching and waiting, we expected to be into it at any moment and most of us had written last requests in the hope that they might be honoured if any got away. We were under no illusion as to what could happen but we didn’t join the Army just for a picnic. When you are face to face with possible and sudden death, things don’t matter much, but one has wistful thoughts of what could have been, but few regrets. I don’t know, now, what my feelings really were, but I know I did think often of Cooma and a girl back there, and remembrance of Kosciusko and tree lined Lambie Street seemed startlingly acute. It gets you that way.

GUNBOAT v PLANE

Then all of us in that particular area saw one of the most gallant actions of all. Out in the Bay, for all the time we had been on the island, two or three little gun boats with stings like wasps patrolled in and around the entrance day and night. They were on watch for possible submarines I suppose, and never for one moment was that entrance left unguarded. We got so used to seeing them that we took them just as a matter of course. On this particular morning, although some of the fiercest fighting of the war, was going on eight or nine miles away, everything seemed peaceful. Birds and butterflies were in evidence and the little black kitten I told you of earlier was chasing his tail quite happily. Suddenly, the all-too-familiar drone of a plane was heard. As usual, we swore forcibly and plentifully, I because I was trying to write a letter (for something to do) and my cobber was trying to light the fire for lunch. Every time Jerry came over we had to put out the fire ___ we were always putting the damn thing out! The plane swooped over our heads, banked, swooped back again and then flew over the Bay. Idling in the calm sea our little gunboat took no more notice than usual until the Jerry flew straight at it and sprayed it with bullets as well a dropping a few bombs. Well, you’ve see the pet cat go when the youngster puts a bunger under its tail, and so did that gun boat. It didn’t run away, but it seemed to fairly leap out of the water as the engines were slammed into top speed. Around and around in tight circles it went, just like an angry swan, and time after time the bomber which looked twice as big as the gun boat, flew backwards and forwards over it, machine-gunning all the time. And bullets flew back at it. The gallant little crew hurled all they had at the plane and it seemed to be spouting flame. This went on for about five minutes and we were feeling very sorry for the brave little vessel – it looked to us much like cat and mouse. Then, suddenly, the plane turned on its side and fell into the sea, sinking immediately. It was all so sudden that we just stared open-mouthed and then I guarantee cheers echoed all round the Bay. The gunboat just slowed down and all was as peaceful as before, though we could hardly believe that a few moments before four or five men drowned before our eyes. Still, he who takes the sword perishes by the sword -and for a better title, I’d say simply retribution.

MARCHING ORDERS

A couple more days passed and still reports spoke of everything under control, but as we often saw the big German troop carriers we knew that the Jerries must be making pretty desperate efforts. The villagers were quietly waiting, but a lot had taken up to the hills, especially the old and infirm. Otherwise they were as resolute as ever and day and night kept their vigilant watch. Then, quite suddenly a message came to say that we had to prepare to move, whether it was forward or backward we didn’t know. We just packed our pitifully few belongings, gave our rifles the once over and waited for marching orders. They came at dusk and quietly we lined up on the dusty little road, grim and quiet, but longing for a cigarette. We marched off down to the main road and turned right, the opposite direction to the fighting. Had more Jerries landed behind us? Had the Jerries in front broken through? Was it another evacuation? We couldn’t answer these questions, but evacuation; we dreaded the thought of it. After the horror of getting away from Greece, when one direct hit could blow a ship out of water if the dive-bombers got at us. We escaped last time, but we couldn’t hope to again, not under those conditions.

Right up to three in the morning we plodded along up the winding steep hills, through still silent villages. A few dogs barked, but except for that we might just as well have been marching through the silence of the desert again. Where we were going we didn’t know , and at three o’clock in the morning we didn’t care much either. Three men were taken suddenly ill and an officer seeing them fall out of line wanted two men to look after them till morning and get them picked up by an ambulance. Another chap and I volunteered, or really were asked to, so, as the others marched off into the night, we remained behind. Almost at dawn an ambulance came along and we put these chaps in with the wounded already inside, but kept marching ourselves. Before long the Jerries were around, strafing the roads, and as far as possible we kept going, while every few minutes having to dive into a ditch. We didn’t know where our unit had gone to, but we just followed our noses and hoped for the best.

Soon trucks crammed with troops passed us and we knew something had happened, or was going to happen, but, tired and thirsty, we kept plodding along. At last we came to a village and a well. Above there was a notice “Last water for 12 miles.” I looked ahead of me and saw the road winding high up the mountains and knew that before I was halfway up there I would be very thirsty again. We found a couple of bottles and filled them and continued on our way through the village, on the first stage of our trek over the mountains. What we didn’t know was that our unit had branched off on another road before the village and had gone on to another town.

GERMAN BARBARITY

Just outside of the village from the top of the hill we looked back at the neat stone houses and then witnessed German savagery and barbarity at its worst. While we were looking back, from out of the clouds came twenty bombers. Twice they circled over us and we, as usual cursed them. Then all hell broke loose. The Germans dropped salvo after salvo of high explosive on this humble peasant community and literally blasted it to pieces. Before our eyes we saw those neat little cottages disintegrate into rubble and dust, while flame and smoke enveloped everything. A fear crazed horse galloped past and two little children crouching in the same ditch as ourselves cried with terror. Down in that inferno pleasant peaceful folk who had done no harm to anyone perished because of a madman’s dream. It wasn’t war, but something that has characterised the Nazi regime all along – sheer bloody massacre. We were sick at heart and at that moment no white flag or Red Cross would have saved any Nazi that might have fallen into our hands. The planes flew over and we marched on.

WALKING WITH DEATH

That night we slept in a cave, too tired to bother with the cold, but our rifles remained loaded with the safety catch off. We slept soundly and woke next morning to the tramp of marching feet. Kiwis, Tommies, Aussies, Cypriots, Sailors and Air Force men in a thin stream were all wearily along the road we didn’t know where it would lead to, and strangely enough, hadn’t thought of that. Joining the bitter file of men who had to obey orders, we found that we were nearly at the top of the mountains and over half way across the island. We kept going, there wasn’t anything else to do. Had we been told to stop, we would have, we could have held our positions indefinitely up there. Soon the Luftwaffe was on the job again and every inch of the road spelt sudden death every few minutes. Time and again bombs hurtled down and half the road would slide a thousand feet into the valley below. Sometimes we found dead men, sometimes a hole in the ground, fragments of metal and a few bits of flesh spattered on the sides of the huge rocks indicated dead men. Occasionally we saw an overturned lorry or one burnt out – mute evidence of good enemy shooting.

At last we reached the top of the mountains, and far, far below us we could see the sea and for twenty or thirty miles around the coast. Fields below us looked like tiny scattered pieces of a jig-saw puzzle, tiny villages and still tinier toy like houses. The road down twisted and turned down like a mad snake. Often by walking, slipping and sliding down the steep lava cliffs, one could cross the road four times in a hundred and fifty yards. Sometimes, bombs had dislodged pieces of rock the size of a house and they came thundering down in a fearsome avalanche. Occasionally a truck, sometimes empty, sometimes with troops, went over the edge. It was horrible.

A NERVE BREAKING WAIT

It was here coming down this road of terror that I had my narrowest escape and worst experience. Every few hundred yards this road had large water channels running under it. They were ideal shelters, and a quick dive into one often got me out of the way of machine gun bullets. On this occasion fifteen of us got into one for a spell. Planes were about so it was a good excuse. Fifty yards up the road there was a truck that had got so far but no further. A flight of bombers, letting fly at everything they saw, concentrated on this truck and us poor devils only that fifty yards away. Well to know that Jerry was aiming at the truck and a moral to hit us, was no pleasant thought and as the air fairly quivered with the shrieks of bombs and the whole earth bucked like an earthquake, we prayed, prayed like none of us have ever prayed since childhood. One bomb just missed us, not the truck, and the concussion was so terrific and the noise so awful that it nearly finished us. Not one of us could hear ourselves or anything else for hours after. This went on for half an hour and every bomb fell within a hundred yards of us. We went into that culvert as young men, we came out aged ten years.

THE NAVY WAITS TO SAVE

I don’t know how we finally got to the bottom of those mountains because Jerry was at us all the time. It was getting dark by the time we reached the security of a cave, and nearby, we found hundreds of other men and an English family, mother, young daughter, son and other members, that had come through all that we had. As it grew dark, the pin points of flame high up on the road down which we had come indicated burning trucks and occasional brilliant flashes indicated bombers using them for targets. Then we heard the boats – the Navy – were coming to take off those whom they could at a nearby port. At two o’clock in the morning in the dim light of a very young moon, we arrived at the little village wharf where the Navy had their cutters waiting. Without confusion, in almost perfect silence, we were marshalled into them and rowed out to the sleek waiting destroyers. One after another, those that could, climbed the ladder hung over the side and were led below. Half asleep, I was taken into a clean tidy mess-room and before I could blink twice a great steaming plate of stew was placed in front of me. But never did stew look or smell so beautiful. Around me others sat down and lifted their spoons.

Then a tall bearded Kiwi, eyes bloodshot, with a dirty rag tied around his head stood up and spoke in a quiet deep voice – “One moment, lads,” he said, then bowed his head “For what we are about to receive, may the Lord make us truly thankful, Amen.”

And, never have such simple words had so great a silent echo.

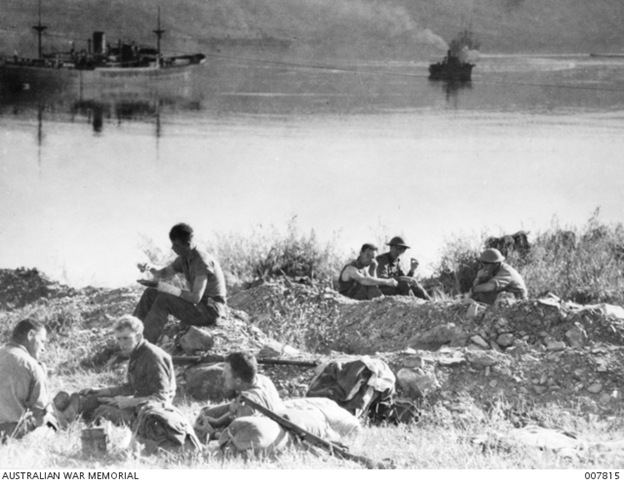

Australian War Memorial photo (007815 ) of men waiting to be picked up.

(His family considers it very likely that it is Pte White sitting in the foreground as that soldier’s profile matches very closely that depicted in a photograph of a young Pte White.)